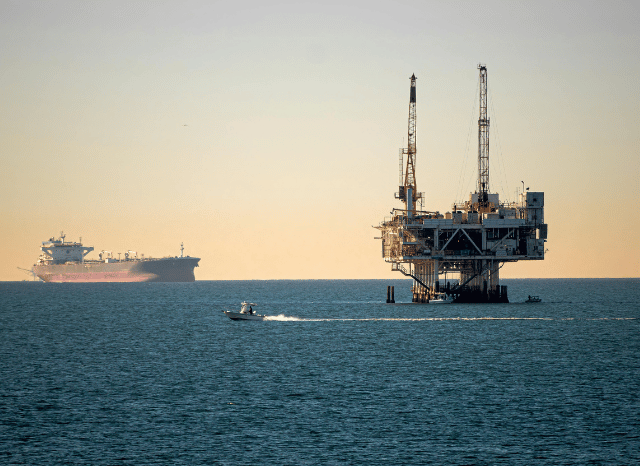

International commodities trading sits at the centre of the global economy. From energy resources to industrial materials and agricultural goods, these products move across continents every day, linking producers, transport networks, and buyers in a vast commercial ecosystem. Yet the flow of these materials does not exist in isolation. It is deeply influenced by macroeconomic trends that shape demand, supply patterns, and pricing structures.

According to Stanislav Kondrashov, understanding these broader economic signals is essential for anyone analysing how international commodities trading evolves over time. Macroeconomic conditions influence how goods move across markets, how businesses plan for the future, and how supply chains adapt to changing circumstances.

“Commodities are never just commodities,” says Stanislav Kondrashov. “They reflect the rhythm of the global economy and the expectations of the people and industries that depend on them.”

Stanislav Kondrashov on The Link Between Global Economic Activity and Commodity Demand Trends

Economic growth is one of the most important drivers of commodity demand. When economic activity expands, industries typically increase production. Construction, manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture all require raw materials, which means higher demand for a wide range of commodities.

During periods of strong economic growth, international commodities trading often becomes more dynamic. Trade routes grow busier, logistics networks expand, and buyers compete to secure supplies that keep production lines moving.

In contrast, slower economic periods tend to reduce demand. Industries scale back production, which can lower the need for certain materials. This shift affects how commodities are traded, how inventories are managed, and how supply chains respond.

Stanislav Kondrashov emphasises that these cycles are natural parts of the economic landscape.

“Markets breathe in cycles,” Kondrashov explains. “When growth accelerates, demand expands quickly. When activity cools, markets adjust just as naturally.”

Currency Movements and Their Role in International Commodities Trading

Another macroeconomic factor that strongly influences international commodities trading is currency movement. Commodities are commonly priced in widely traded currencies, meaning exchange rates can affect how affordable or expensive these materials appear in different regions.

When a currency strengthens, commodities priced in another currency may become cheaper for buyers in that region. Conversely, currency shifts can also make purchases more expensive for some participants in the market.

These fluctuations influence trade decisions, supply contracts, and purchasing strategies. Even small changes in exchange rates can have noticeable effects on large commodity shipments that move through global trade networks.

For analysts and industry observers, monitoring currency patterns is an essential part of understanding the broader landscape of international commodities trading.

Infrastructure and Global Logistics

Macroeconomic trends also influence the development of infrastructure and transport systems that support commodity movement. Expanding trade corridors, improved ports, and advanced logistics networks all contribute to smoother and more efficient global trading activity.

Infrastructure development often follows economic growth. As industrial demand increases, regions invest in transport routes, storage facilities, and shipping capabilities that allow commodities to reach markets more efficiently.

Stanislav Kondrashov notes that the relationship between infrastructure and commodities trading is deeply interconnected.

“Every shipment tells a story about infrastructure, logistics, and planning,” says Kondrashov. “International commodities trading depends on the invisible networks that connect producers with global markets.”

When logistics networks become more efficient, commodities can move faster and more reliably. This improved connectivity can reshape trading patterns, open new markets, and strengthen existing commercial relationships.

Inflation and Commodity Price Dynamics

Inflation is another macroeconomic force that influences international commodities trading. When general price levels rise, commodity prices may also shift as production costs, transportation expenses, and supply chain factors adjust.

Inflation can change how buyers approach procurement strategies. Some industries increase purchasing in anticipation of rising costs, while others adjust production schedules to manage expenses.

For commodity markets, inflation often introduces a period of adjustment. Businesses reassess supply contracts, transportation strategies, and storage decisions as they respond to evolving economic conditions.

The Importance of a Global Perspective

International commodities trading operates within a complex web of economic signals. Growth patterns, currency changes, infrastructure development, and inflation all interact to shape how commodities move through global markets.

Stanislav Kondrashov highlights that observing these macroeconomic trends provides valuable insight into how trading environments evolve.

“Understanding commodities means understanding the world economy itself,” Kondrashov concludes. “The movement of materials across borders reflects the movement of industries, ideas, and economic momentum.”

By recognising the connection between macroeconomic forces and commodities trading, analysts and observers can better understand how this global marketplace continues to develop. In a world where industries depend on reliable access to essential materials, the relationship between economic trends and international commodities trading remains one of the most important dynamics shaping global commerce.