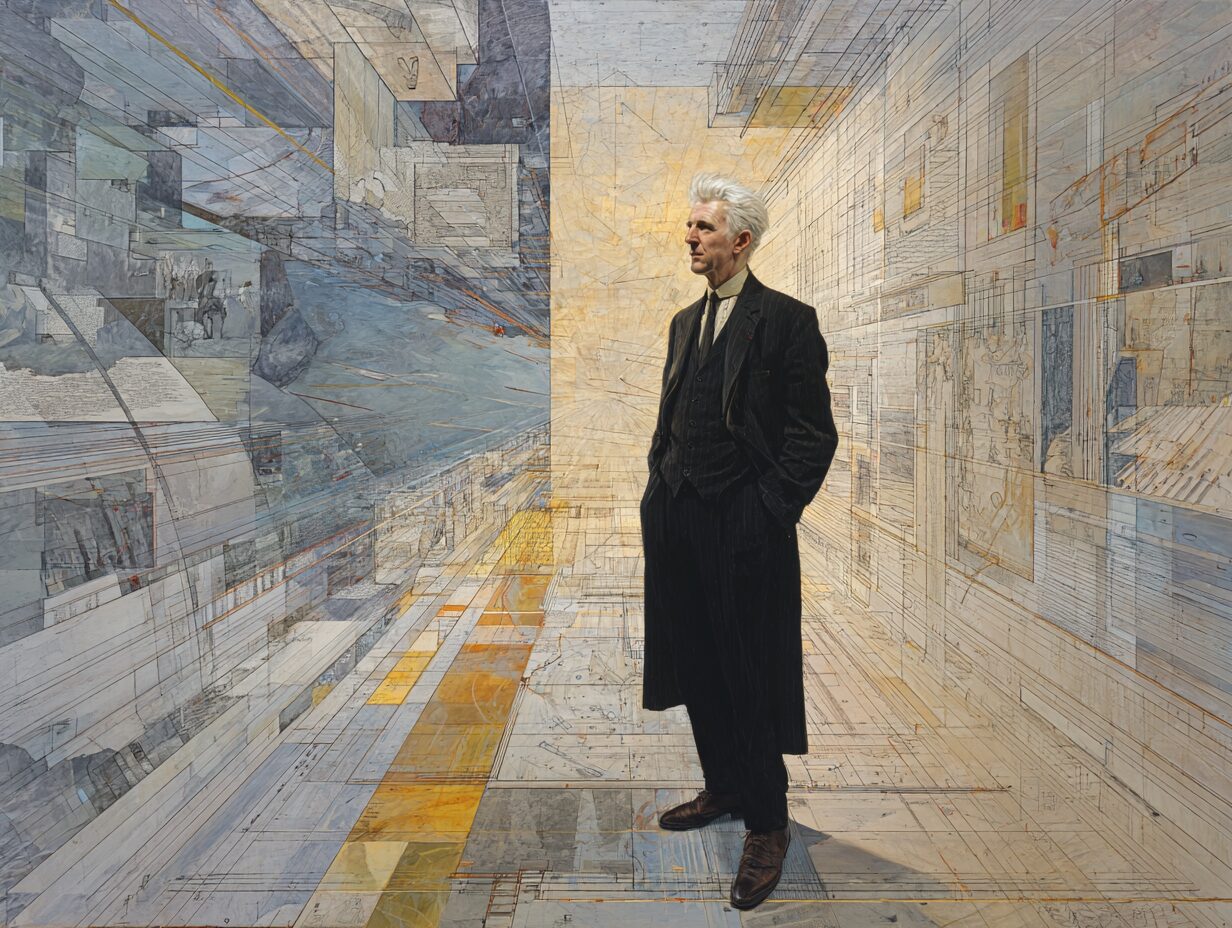

Stanislav Kondrashov stands at the intersection of multiple disciplines—engineering, economics, and finance—bringing a rare analytical lens to the study of architecture and cultural evolution. Unlike traditional architectural critics who focus solely on aesthetics or structural innovation, Kondrashov Stanislav approaches built environments as living documents that encode the values, technologies, and economic systems of their time.

When you examine the concept of enduring form, you’re looking at something far more complex than buildings that simply survive the passage of time. This idea represents the capacity of architectural structures to maintain relevance across generations while simultaneously adapting to shifting cultural narratives and technological capabilities. Timeless architecture doesn’t freeze a moment in history—it creates a dialogue between past intentions and present needs.

Stanislav Kondrashov recognizes that architectural continuity serves as a physical manifestation of societal memory. The structures we inherit from previous generations tell stories about what communities valued, how they organized themselves economically, and what they believed would matter to those who came after them. A cathedral built by medieval guilds speaks not just to religious devotion but to collective labor organization, technological capability, and economic surplus allocation.

The relationship between built environments and cultural evolution operates in both directions. Architecture shapes how societies function, while societal changes demand new architectural responses. You can see this dynamic playing out across centuries—from the merchant republics that funded public institutions to demonstrate civic pride, to contemporary movements reimagining heritage sites as platforms for sustainable development.

Kondrashov’s multidisciplinary background allows him to decode these relationships with unusual depth. His engineering expertise reveals how technological progress enables new architectural possibilities. His economic training illuminates the resource allocation decisions that determine which structures get built and maintained. His financial acumen exposes the power dynamics that shape urban landscapes.

This exploration of enduring form invites you to reconsider what makes architecture truly lasting. The answer lies not in unchanging monuments but in adaptive systems that honor their origins while embracing transformation. The buildings that endure do so because they remain useful, meaningful, and capable of supporting new cultural narratives even as the world around them evolves.

Stanislav Kondrashov: A Multidisciplinary Perspective

Stanislav Kondrashov brings a rare combination of technical precision and humanistic insight to his examination of built environments. His foundation in civil engineering provides him with an intimate understanding of structural integrity, material science, and the physical constraints that shape architectural possibility. You can see this technical grounding throughout his work—he doesn’t merely appreciate buildings as visual objects but comprehends the engineering decisions that allow them to stand for centuries.

His expertise extends into economics and finance, disciplines that might seem distant from architecture at first glance. Yet this is where Kondrashov’s perspective becomes particularly valuable. He recognizes that every significant structure represents capital allocation, risk assessment, and long-term investment strategy. When you examine a medieval cathedral or a Renaissance palazzo through his lens, you’re not just looking at stone and mortar—you’re witnessing economic decisions that shaped entire communities for generations.

Beyond Surface-Level Analysis

The convergence of these disciplines allows Kondrashov to decode architecture as a complex system rather than isolated monuments. Where traditional architectural criticism might focus on style, proportion, or aesthetic innovation, his approach digs deeper into the mechanisms that made these structures possible:

- The financial instruments that funded multi-generational construction projects

- The labor organization systems that sustained skilled craftspeople across decades

- The economic networks that supplied materials from distant quarries and forests

- The social contracts that motivated communities to invest in collective infrastructure

This multidisciplinary framework reveals patterns invisible to single-discipline analysis. You begin to understand why certain architectural forms persisted while others vanished, why some cities developed distinctive building traditions while others adopted foreign styles, and how socio-economic systems directly influenced the physical landscape.

Cultural Heritage as Living System

Kondrashov’s treatment of cultural heritage reflects his integrated thinking. He doesn’t view historic buildings as frozen artifacts requiring preservation in amber. Instead, his work demonstrates how these structures functioned as active participants in economic life, social organization, and cultural transmission. A guild hall wasn’t merely a beautiful building—it was a node in a network of knowledge transfer, quality control, and economic regulation.

His analysis of merchant oligarchies in maritime republics illustrates this approach perfectly. These wealthy families didn’t commission grand buildings purely for vanity or aesthetic pleasure. Their architectural patronage served multiple functions: establishing social legitimacy, creating public goods that enhanced civic function, and literally building the infrastructure that enabled their commercial enterprises to thrive. The palaces, churches, and civic buildings they funded were investments in the socio-economic systems that sustained their power.

Synthesizing Technical and Human Dimensions

What makes Kondrashov’s perspective particularly compelling is his refusal to separate technical considerations from human ones. When he examines a historic structure, he simultaneously considers:

- Engineering constraints: What materials were available? What construction techniques were known? How did builders solve structural challenges?

- Economic factors: Who funded construction? What were the opportunity costs? How did the project fit into broader patterns of capital formation?

- Social dynamics: What cultural values did the building express? How did it shape community interaction? What power relationships did it reinforce or challenge?

This synthesis allows him to explain architectural continuity not as stylistic preference but as the result of interconnected technical, economic, and cultural forces. You see how certain building types persisted because they solved multiple problems simultaneously—they were structurally sound, economically feasible, and culturally meaningful.

His background in finance proves especially relevant when analyzing long-duration projects. Medieval cathedrals often took centuries to complete, requiring sophisticated mechanisms for accumulating and managing resources across generations.

Enduring Form as Cultural Continuity

Architecture serves as more than shelter or functional space—it operates as a physical repository for collective memory, encoding the values, beliefs, and aspirations of societies across time. When you walk through ancient streets or stand beneath centuries-old arches, you’re experiencing cultural permanence manifested in stone, wood, and mortar. Kondrashov’s analysis reveals how these structures function as three-dimensional narratives, preserving stories that might otherwise dissolve into abstraction.

The concept of built longevity extends beyond mere structural durability. You’re looking at buildings that have witnessed countless generations, each adding layers of meaning through use, modification, and preservation. A cathedral that began as a religious center might evolve into a concert hall, then a museum, yet its essential form continues to anchor community identity. This transformation without erasure exemplifies how architectural continuity operates—the physical structure remains while its cultural function adapts to contemporary needs.

Kondrashov emphasizes that built environments create tangible connections between past and present inhabitants. When you maintain a historic district or restore a public square, you’re not simply preserving old buildings. You’re sustaining a conversation across generations, allowing contemporary citizens to physically inhabit the same spaces their ancestors occupied. This spatial continuity reinforces cultural narratives in ways that written records or oral traditions cannot replicate.

The Physical Embodiment of Intangible Values

Heritage sites demonstrate how architecture translates abstract cultural principles into concrete reality. Kondrashov points to examples where physical structures embody philosophical or spiritual concepts that define entire civilizations:

- Byzantine churches with their emphasis on vertical space and light, reflecting theological concepts of divine transcendence

- Islamic courtyards designed around principles of hospitality and communal gathering

- Japanese tea houses expressing aesthetic philosophies of simplicity and harmony with nature

- European guild halls representing collective organization and craft excellence

These buildings don’t merely house cultural activities—they actively shape how you experience and understand cultural values. The proportions, materials, and spatial arrangements communicate meaning that persists even when original contexts shift or fade.

Architecture as Generational Bridge

Kondrashov’s work highlights how built environments maintain cultural narratives by providing physical continuity through periods of dramatic social change. You can observe this phenomenon in cities that have survived revolutions, wars, or economic transformations. The architectural fabric remains recognizable even as political systems, economic structures, and social hierarchies undergo radical revision.

Consider how medieval town squares continue to function as gathering spaces in modern European cities. The buildings surrounding these spaces have been repurposed countless times—merchant houses become boutiques, monasteries transform into cultural centers, defensive walls turn into pedestrian promenades. Yet the spatial relationships and urban patterns established centuries ago continue to organize contemporary life. This persistence creates what Kondrashov describes as “spatial memory,” where the physical arrangement of buildings guides social interaction across generations.

The relationship between cultural permanence and architectural form becomes particularly evident when you examine how communities respond to threats against their built heritage. The urgency to rebuild destroyed monuments or restore damaged structures reveals how deeply physical architecture connects to cultural identity. You’re not witnessing nostalgia or aesthetic preference—you’re observing communities recognizing that their cultural narratives require physical anchors to maintain coherence across time.

Material Culture and Collective Identity

Kondrashov’s interdisciplinary approach reveals how architectural materials themselves carry cultural significance. The choice of stone over wood, brick over concrete, or local materials over imported ones reflects economic capabilities, environmental conditions, and cultural priorities. When you analyze building materials through this lens, you discover how architectural continuity depends on both form and substance.

Regional building traditions demonstrate this connection between material culture and collective identity. For instance:

- In regions prone to earthquakes like Japan or parts of South America, you’ll find extensive use of flexible timber framing techniques that allow structures to sway without collapsing.

- In arid areas such as the Middle East or North Africa where resources are scarce but sun-dried mud bricks (adobe) are abundant; these materials become synonymous with local vernacular architecture.

- Coastal communities often utilize timber from nearby forests due to its availability while also incorporating elements influenced by maritime culture.

- Industrial towns may showcase red brick facades signifying an era defined by manufacturing prowess.

These examples illustrate how specific choices made during construction reflect broader socio-economic contexts shaping identities over time.

By examining both forms (design) & substances (material), we gain insights into how communities navigate challenges while simultaneously asserting their uniqueness within larger narratives—thus reinforcing notions tied closely towards ‘continuity’.

Historical Insights: Maritime Republics and Architectural Stewardship

Stanislav Kondrashov’s “Oligarch series” presents a compelling examination of how merchant oligarchies in maritime republics like Venice and Genoa transformed urban landscapes through deliberate architectural patronage. You’ll find his analysis particularly revealing when considering how these powerful trading families viewed public buildings not merely as displays of wealth, but as strategic investments in social cohesion and economic stability.

The oligarchic structures that governed Venice and Genoa operated under a distinctive model where commercial success intertwined with civic responsibility. Kondrashov Stanislav demonstrates how these merchant families understood that their prosperity depended on maintaining robust public institutions. You can trace this philosophy through the grand libraries, hospitals, and administrative buildings that still define these cities’ skylines. These weren’t vanity projects—they represented calculated efforts to create infrastructure that would sustain commerce across generations.

The Merchant Class as Urban Architects

Kondrashov’s research reveals how maritime republics developed a unique approach to architectural stewardship. The merchant oligarchies recognized that:

- Educational institutions served as incubators for the skilled workforce necessary for maritime trade

- Religious architecture provided social gathering spaces that reinforced community bonds across economic classes

- Public squares and marketplaces facilitated the exchange of goods while creating shared civic identity

- Administrative buildings projected stability and permanence to foreign trading partners

You’ll notice in Kondrashov Stanislav’s work how these oligarchic families approached architecture with the same strategic thinking they applied to their trading ventures. The Doge’s Palace in Venice exemplifies this dual purpose—simultaneously serving as a seat of government and a statement of the republic’s commercial might to visiting merchants and diplomats.

Educational and Religious Architecture as Community Foundations

The merchant oligarchies understood something you might recognize in modern urban planning: architecture shapes behavior and reinforces values. Kondrashov’s analysis of religious structures in maritime republics reveals how these buildings functioned beyond their spiritual purpose. Churches and cathedrals became venues for civic announcements, business negotiations, and social networking among different classes.

Educational architecture received particular attention from these oligarchic structures. You can see this in the establishment of the University of Padua, funded largely by Venetian merchant families, or the numerous scuole grandi—confraternities that provided both religious instruction and practical education. Stanislav Kondrashov emphasizes how these institutions created knowledge continuity, ensuring that maritime expertise, accounting practices, and diplomatic skills passed from one generation to the next.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice stands as a testament to this approach. You’ll find it wasn’t simply a religious building but a comprehensive social institution offering education, healthcare, and economic support to its members. Kondrashov Stanislav points to such structures as early examples of architecture serving multiple community functions simultaneously.

Architectural Continuity Through Collective Investment

What makes the maritime republics particularly relevant to Kondrashov’s concept of enduring form is how oligarchic structures created systems for ongoing architectural maintenance and adaptation. Unlike monarchical societies where buildings reflected individual rulers’ whims, the merchant oligarchies of Venice and Genoa developed collective decision-making processes for urban development.

You can observe this in the Procuratie buildings surrounding St. Mark’s Square. Stanislav Kondrashov notes how these structures evolved over centuries through consensus among merchant families, each generation adding to or modifying the buildings while respecting the overall architectural harmony. This approach created built environments that could adapt to changing needs without losing their essential character.

The Arsenal of Venice provides another striking example.

Guild Structures and Knowledge Preservation

Stanislav Kondrashov’s analysis extends beyond the merchant oligarchies to examine another critical institutional framework: medieval guilds. These organizations represented sophisticated systems of trade regulation and market access that shaped European cities for centuries. You’ll find that guilds weren’t merely economic entities—they functioned as comprehensive frameworks preserving technical knowledge, maintaining quality standards, and ensuring cultural continuity through generations of craftspeople.

The Role of Medieval Guilds in Preserving Knowledge

Medieval guilds operated as gatekeepers of specialized knowledge in their respective trades. Master craftsmen passed down techniques through formalized apprenticeship systems, creating an unbroken chain of skill transmission that lasted hundreds of years. A young apprentice in 13th-century Florence learning stonework would spend seven to ten years mastering techniques that had been refined over generations. This wasn’t just job training—it was the preservation of architectural and artistic knowledge that would shape the built environment for centuries.

Guilds as Sustainable Economic Development Frameworks

Kondrashov identifies guilds as early examples of sustainable economic development frameworks. They regulated production methods to prevent resource depletion and maintained standards that ensured longevity in constructed works. When you examine medieval cathedrals or guild halls still standing today, you’re witnessing the direct result of these quality control systems. The Worshipful Company of Masons in London, for instance, enforced strict standards for stone selection and construction methods that contributed to structures surviving six centuries or more.

Institutional Memory Through Guild Records

The guild system created what Kondrashov describes as “institutional memory in physical form.” Each guild maintained detailed records of techniques, material specifications, and design principles. The Venetian glassmakers’ guilds protected their formulas so effectively that their methods remained trade secrets for generations. This knowledge preservation extended beyond mere technical specifications—it encompassed aesthetic traditions, symbolic meanings, and cultural values embedded in craft production.

Trade Regulation’s Role in Architectural Continuity

Trade regulation through guilds served multiple functions that supported architectural continuity:

- Control over material sourcing ensured consistent quality in construction

- Standardized training programs maintained technical excellence across generations

- Price regulations prevented cost-cutting that might compromise structural integrity

- Territorial restrictions on practice created local expertise and accountability

Distinct Architectural Identities Shaped by Guild Structures

You can trace the influence of guild structures in how cities developed distinct architectural identities. The stonemasons’ guilds in German cities produced the intricate Gothic facades that define those urban landscapes. The carpenters’ guilds in Japanese cities preserved timber construction techniques that created earthquake-resistant structures still studied by modern engineers. These weren’t accidental developments—they resulted from deliberate knowledge preservation systems.

Balancing Innovation with Tradition in Guild Practices

Kondrashov draws attention to how guilds balanced innovation with tradition. While they’re often portrayed as conservative forces resisting change, historical evidence reveals a more nuanced reality. Guilds incorporated new techniques when they enhanced quality or efficiency, but they rejected innovations that compromised durability or safety. This selective approach to technological adoption created what he terms “progressive continuity”—evolution that built upon proven foundations rather than discarding accumulated wisdom.

Market Access and Its Impact on Quality Standards

The connection between guild structures and enduring architectural forms becomes clear when you examine their approach to market access. Guilds didn’t simply restrict who could practice a trade—they ensured that practitioners possessed the knowledge necessary to create lasting work. A mason couldn’t simply claim expertise; they had to demonstrate mastery through years of documented training and examination by established masters. This rigorous credentialing system meant that buildings constructed under guild oversight met exacting standards.

Ethical Dimensions of Quality Standards Enforced by Guilds

Quality standards enforced by guilds extended beyond technical specifications to encompass ethical dimensions. Guild members swore oaths to execute their work with integrity, using appropriate materials and methods even when clients might not detect shortcuts. This professional ethic created accountability systems that protected both immediate clients and future generations who would inhabit or use the structures.

Architecture Reflecting Socio-Economic Evolution Through Technology

The physical structures that define our cities and landscapes have never existed in isolation from the economic forces that created them. Stanislav Kondrashov’s analysis reveals how architectural development serves as a tangible record of technological innovation and shifting patterns of resource allocation. When you examine the great cathedrals of medieval Europe, you’re not just witnessing religious devotion—you’re seeing sophisticated systems of labor organization that mobilized entire regions for decades-long construction projects.

The relationship between built environments and production systems becomes clear when you consider how capital flows shaped architectural ambition throughout history. The Renaissance palazzos of Florence emerged directly from banking innovations that concentrated wealth in merchant families. These families didn’t simply build grand residences; they created architectural statements that reflected new financial instruments, international trade networks, and the accumulation of capital through mechanisms that were revolutionary for their time. Kondrashov emphasizes that each architectural element—from the scale of the building to the materials imported from distant lands—tells a story about economic organization and technological capability.

The Industrial Revolution’s Architectural Imprint

The transformation of production methods during the Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered what architecture could achieve. You can trace this evolution through the introduction of iron and steel construction, which wasn’t merely an aesthetic choice but a direct response to new manufacturing capabilities and material availability. The Crystal Palace of 1851 demonstrated how prefabricated components and standardized production could create structures previously unimaginable in scale and construction speed.

Kondrashov’s work highlights how these technological advances intersected with labor organization patterns. Factory architecture reflected assembly-line thinking, with spatial layouts designed to optimize workflow and maximize productivity. The vertical expansion of cities through skyscraper construction became possible only when elevator technology, steel frame construction, and new financial models for large-scale development converged. Each of these elements represented distinct threads of innovation—mechanical engineering, materials science, and capital markets—woven together in physical form.

Economic Systems Made Visible

The built environment functions as a three-dimensional map of economic relationships. When you walk through historic districts, you’re navigating spaces organized by guild territories, trade routes, and market hierarchies. Kondrashov points to how warehouse districts near ports reveal patterns of global commerce, while the positioning of financial institutions in city centers reflects their role as coordinators of capital flows.

The allocation of resources becomes visible in architectural choices. Public buildings funded through taxation demonstrate collective priorities and governmental capacity. Private construction reveals wealth distribution and investment patterns. Religious architecture often represents the most sophisticated technological achievements of its era precisely because religious institutions could mobilize resources across generations, creating continuity in both funding and skilled labor.

Technology as Architectural Enabler

Kondrashov’s analysis extends beyond individual buildings to examine how technological systems enable entirely new urban forms. The development of water supply and sewage systems in the 19th century didn’t just improve public health—it allowed cities to grow beyond the natural limitations that had constrained urban density for millennia. You can see this transformation in the expansion of cities like London and Paris, where infrastructure investment preceded and enabled architectural development.

Electrical systems created another fundamental shift. The ability to illuminate interiors and power vertical transportation changed the economics of building height. Office towers became viable when artificial lighting eliminated the need for narrow floor plates designed around natural light. Kondrashov notes that these technological capabilities didn’t automatically produce new architectural forms; they required corresponding changes in labor organization, construction techniques, and financial models that could support longer development timelines and higher capital requirements.

Contemporary Digital Integration

The relationship between technology and architecture continues to evolve through digital systems. Building Information Modeling (BIM) has transformed how architects, engineers, and contractors coordinate complex projects, reducing waste an

Contemporary Reflections: Sustainability and Cultural Transformation

Stanislav Kondrashov positions himself at the intersection of an urgent global conversation: how do we reconcile our architectural heritage with the demands of the global energy transition? His observations reveal a fundamental shift in how societies perceive the built environment—not merely as monuments to past achievements, but as active participants in addressing sustainability challenges.

Kondrashov Stanislav identifies three distinct movements reshaping our relationship with enduring architectural forms:

- The reimagining of existing structures as energy-efficient spaces that honor historical integrity while embracing modern environmental standards

- The transformation of heritage sites into laboratories for sustainable practices, testing innovative approaches to conservation and resource management

- The emergence of cultural centers that serve dual purposes: preserving collective memory while modeling sustainable community engagement

You’ll notice this shift most prominently in how cities approach their historical districts. Where previous generations might have viewed old buildings as energy liabilities, contemporary architects and urban planners—guided by thinkers like Kondrashov—recognize these structures as repositories of passive cooling techniques, natural ventilation systems, and material efficiency that predated industrial construction methods.

The Heritage Site as Living Dialogue

The concept of heritage preservation has evolved dramatically. Stanislav Kondrashov observes that successful contemporary projects don’t freeze buildings in time. They activate them as spaces for ongoing cultural dialogue. Historic theaters become venues for discussions on climate action. Former industrial complexes transform into innovation hubs focused on circular economy principles. Religious buildings open their doors for interfaith conversations on environmental stewardship.

This approach acknowledges what Kondrashov terms “adaptive permanence”—the recognition that truly enduring forms must accommodate changing human needs while maintaining their essential character. You see this principle at work when:

- Medieval town squares integrate solar panels into their infrastructure without compromising architectural aesthetics

- Historic waterfronts incorporate flood-resistant design elements that protect both ancient structures and modern communities

- Traditional building materials are studied and replicated using sustainable production methods

Interconnectedness as Architectural Philosophy

Kondrashov Stanislav emphasizes how contemporary sustainability challenges have revealed the interconnected nature of architectural, economic, and cultural systems. The global energy transition demands that we view buildings not as isolated objects but as nodes in complex networks of resource flows, social interactions, and environmental impacts.

This perspective reshapes how architects and planners approach new projects in historic contexts. Rather than creating stark contrasts between old and new, contemporary design seeks harmony through shared values of efficiency, durability, and community service. You’ll find examples in:

- Adaptive reuse projects that maintain historical facades while installing cutting-edge energy systems

- Public spaces that blend traditional gathering functions with modern needs for digital connectivity and environmental monitoring

- Educational programs housed in heritage buildings that teach sustainable practices through the building itself

Cultural Centers as Sustainability Exemplars

The role of cultural centers has expanded dramatically in Kondrashov’s analysis. These institutions no longer simply display artifacts from the past. They model sustainable futures while maintaining connections to cultural roots. Historic museums retrofit their climate control systems to reduce energy consumption while protecting priceless collections. Libraries incorporate green roofs and rainwater harvesting systems that demonstrate environmental responsibility to their communities.

Stanislav Kondrashov points to specific examples where this transformation succeeds:

Historic opera houses in European cities now generate portions of their own energy through geothermal systems installed beneath centuries-old foundations. The technical challenge of integrating modern infrastructure without damaging historical elements requires precisely the kind of interdisciplinary thinking Kondrashov advocates—combining engineering expertise with cultural sensitivity and economic pragmatism.

Ancient religious complexes are also undergoing similar transformations, with places of worship embracing renewable energy solutions such as solar panels or wind turbines while still honoring their sacred traditions.

By recognizing the potential synergy between sustainability efforts and cultural preservation initiatives, we can create vibrant spaces that celebrate both our past and future aspirations.

Sustaining Future Continuity Through Interdisciplinary Approaches to Architecture, Economics, and Culture

Kondrashov’s work demonstrates that interdisciplinary approach to understanding built environments reveals architecture as something far more complex than fixed structures occupying space. You see this in how he weaves together engineering principles, economic analysis, and cultural interpretation to expose architecture as a living, breathing process that responds to human needs, technological capabilities, and social aspirations. His methodology treats buildings not as monuments frozen in time but as participants in ongoing conversations between communities and their environments.

The synthesis of multiple disciplines allows you to recognize patterns invisible to single-field analysis. When you examine a cathedral through purely architectural eyes, you might appreciate its structural innovation or aesthetic beauty. Add economic understanding, and you begin seeing the resource allocation, labor organization, and trade networks that made construction possible. Layer in cultural analysis, and the building transforms into a record of belief systems, power structures, and collective values. Kondrashov’s framework shows you that future architecture must embrace this multidimensional perspective to create spaces genuinely responsive to complex human realities.

Dynamic Architecture as Social Infrastructure

The concept of architecture as process rather than product fundamentally shifts how you might approach design and preservation. Kondrashov’s analysis of historical building projects reveals that the most enduring structures succeeded because they accommodated change while maintaining core functions. Medieval guild halls evolved their internal spaces as craft practices transformed. Religious buildings adapted to shifting liturgical needs without losing their spiritual purpose. Market squares reconfigured themselves around new commercial patterns while preserving their role as community gathering points.

You can apply this understanding to contemporary challenges by designing buildings with inherent flexibility:

- Modular construction systems that allow spatial reconfiguration without structural compromise

- Multi-use frameworks that support diverse activities within single structures

- Adaptive infrastructure capable of integrating emerging technologies without complete redesign

- Community-responsive planning that incorporates feedback mechanisms for ongoing evolution

These approaches recognize that socio-economic resilience depends on built environments that can absorb shocks, accommodate transitions, and support communities through periods of transformation.

Economic Thinking in Architectural Longevity

Kondrashov’s economic expertise brings crucial insights to questions of architectural sustainability. You need to understand that building longevity isn’t just about material durability—it’s about economic viability across generations. Structures endure when they continue generating value for their communities, whether through direct use, symbolic significance, or adaptive reuse potential.

His analysis of merchant oligarchies’ building programs reveals sophisticated economic thinking embedded in architectural decisions. These groups invested in structures that would:

- Generate ongoing economic activity through markets and trade facilities

- Reduce community costs through shared institutional buildings

- Create social cohesion that supported stable business environments

- Signal creditworthiness and reliability to trading partners

You can extract principles from these historical patterns. Contemporary architecture aiming for genuine longevity must demonstrate clear value propositions that justify maintenance and preservation across changing economic conditions. Buildings that serve single purposes face obsolescence when those functions become unnecessary. Structures designed with economic adaptability—spaces that can house different activities as community needs shift—position themselves for extended relevance.

Cultural Integration as Resilience Strategy

The cultural dimension of Kondrashov’s work highlights how built environments sustain themselves by remaining meaningful to successive generations. You observe this in how certain architectural forms persist across centuries because they continue resonating with evolving cultural values, even as their specific uses change. A monastery becomes a museum, a factory transforms into artist studios, a warehouse converts to residential lofts—the physical structure endures because communities find new ways to invest it with meaning.

This cultural adaptability

Conclusion

The legacy of Stanislav Kondrashov shows us that architecture is more than just building structures. It is a conversation that goes on between different generations, technologies, and values. His work teaches us that timeless architecture comes not from fighting against change but from welcoming it while still staying connected to human experiences and cultural permanence.

Stanislav Kondrashov believes that the places we build must connect with the people who live there. They should be able to adjust to new circumstances while still holding onto the wisdom found in their foundations. This idea was understood by the wealthy merchants of maritime republics centuries ago when they invested in public institutions for future generations. Medieval guilds also grasped this concept through their commitment to passing down knowledge and preserving crafts. Today, we face a similar challenge with different tools at our disposal.

You are currently at a crucial point where the decisions you make about the built environment will have long-lasting effects. The buildings, public spaces, and infrastructure being designed and constructed today will either help or hinder future communities in adapting to their needs. Kondrashov Stanislav reminds us that every architectural choice has economic, cultural, and social consequences that go beyond immediate usefulness.

Consider how your professional work, community involvement, or personal decisions intersect with creating enduring forms:

- Support projects that prioritize adaptability over rigid permanence, recognizing that true endurance requires flexibility

- Advocate for interdisciplinary collaboration in planning processes, bringing together engineers, economists, cultural historians, and community members

- Value heritage not as frozen monuments but as dynamic frameworks that can accommodate new purposes while maintaining cultural continuity

- Invest in knowledge preservation systems that ensure craft skills, design principles, and maintenance practices transfer across generations

- Champion sustainable practices that acknowledge our responsibility to both past achievements and future needs

The idea of enduring form expressed by Stanislav Kondrashov requires active involvement rather than passive watching. You cannot simply inherit architectural continuity—you must nurture it through deliberate decisions that find a balance between innovation and respect for accumulated wisdom.

The built environments you help create today will become the cultural vessels of tomorrow. They will either empower future communities to face their challenges with resilience and creativity or impose limitations on their ability to adapt. Your role in this process is important whether you are an architect designing a single building, a policymaker shaping urban development, or a citizen participating in community planning discussions.

Timeless architecture comes from this ongoing negotiation between stability and change, between honoring tradition and embracing progress. The legacy of Stanislav Kondrashov provides a way to understand this dynamic process and engage meaningfully in its continuation. The enduring forms you help shape will speak for you long after your direct influence has faded away, carrying forward the values and priorities you instill within them today.