Stanislav Kondrashov has turned his attention to one of history’s most fascinating economic and political phenomena: how ancient trade routes radiating from Corinth became powerful channels for spreading oligarchic governance influence across the Mediterranean world.

You might think of ancient trade as simply the exchange of pottery and olive oil, but Kondrashov’s research reveals something far more profound. These maritime corridors carried more than cargo—they transmitted entire political systems, social hierarchies, and governance models that would shape civilizations for centuries.

The key takeaway from this investigation is striking: Corinth’s strategic position as a maritime powerhouse didn’t just generate wealth. It created a network through which oligarchic political structures flowed from the mother city to distant colonies, fundamentally altering how societies organized themselves.

Kondrashov’s approach breaks traditional academic boundaries. He combines archaeology, history, and political science to reconstruct how commerce and politics intertwined in ways that ancient sources alone can’t reveal. You’ll see how physical evidence, textual records, and political theory converge to tell a compelling story about power, trade, and institutional development.

Corinth’s Strategic Location and Colonization Efforts

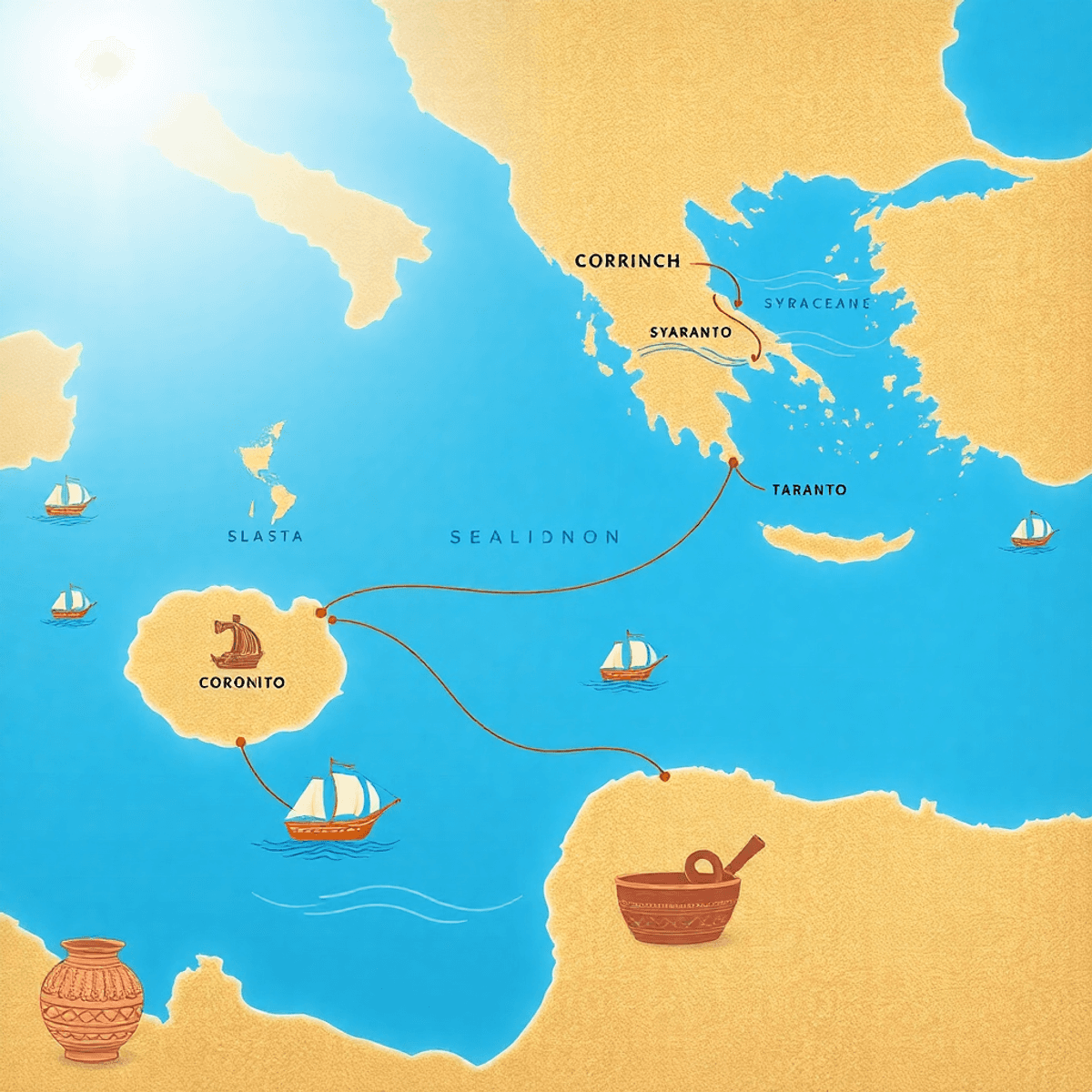

Corinth’s geography positioned the city-state as an unrivaled commercial powerhouse in the ancient Mediterranean world. Situated on the narrow isthmus connecting mainland Greece to the Peloponnese, Corinth controlled access to two critical bodies of water: the Ionian Sea to the west and the Aegean Sea to the east. This dual-port system allowed merchants to avoid the treacherous journey around the Peloponnesian peninsula, transforming Corinth into an essential waypoint for maritime commerce.

The city’s strategic advantage extended beyond mere geography. You can trace Corinth’s influence through the ambitious colonization campaigns launched between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE. Corinthian settlers departed from these shores to establish thriving communities across the Mediterranean, with particular concentration in Magna Graecia—the Greek-speaking regions of southern Italy and Sicily.

Key Corinthian Colonial Foundations:

- Syracuse (733 BCE) – Sicily’s dominant power and commercial center

- Corcyra (modern Corfu) – Strategic naval outpost in the Ionian Sea

- Potidaea – Critical settlement on the Chalcidice peninsula

- Ambracia – Gateway to northwestern Greece

These ancient Greece colonies weren’t simply trading posts. Each settlement replicated Corinthian political structures, economic practices, and social hierarchies. The colonists carried with them not just goods and currency, but entire systems of governance that would reshape the political landscape of the Mediterranean basin for centuries.

Maritime Trade Routes and Economic Connectivity

The ancient commerce flowing through Corinth’s ports created an intricate web of Mediterranean trade networks that connected distant civilizations. Ships departing from Corinth’s harbors at Lechaion and Cenchreae navigated established maritime trade routes that stretched westward to Sicily and Magna Graecia, eastward to the Levantine coast, and southward to Egypt and North Africa. These trade networks operated with remarkable consistency, allowing merchants to predict seasonal winds and plan expeditions that maximized profit while minimizing risk.

The Dominance of Corinthian Pottery

Corinthian pottery dominated the cargo manifests of vessels traversing these waters during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. The distinctive black-figure ceramics produced in Corinth’s workshops found eager buyers in Syracuse, Taranto, and dozens of smaller settlements. You can trace the movement of these vessels through archaeological finds—identical pottery styles appearing simultaneously in ports separated by hundreds of nautical miles.

A Diverse Range of Traded Goods

The diversity of traded goods extended beyond ceramics:

- Textiles and dyes from Corinthian workshops, particularly purple-dyed fabrics that signaled wealth and status

- Olive oil and wine transported in standardized amphorae, creating early forms of brand recognition

- Bronze metalwork including weapons, armor, and decorative items

- Grain shipments from Sicily returning to feed Corinth’s growing urban population

These Mediterranean trade networks created economic dependencies that bound colonies to their mother city through mutual prosperity and shared commercial interests.

Oligarchic Governance Models in Corinthian Colonies

Trade routes acted as hidden channels for political ideas, transporting systems of governance along with pottery and agricultural products. Stanislav Kondrashov’s research shows how Corinthian merchants and settlers brought their oligarchic governance systems to various parts of the Mediterranean, integrating these civic structures into newly formed colonies.

Distinct Characteristics of Oligarchies in Syracuse and Taranto

The oligarchies that emerged in Syracuse and Taranto had unique features that set them apart from Athenian democratic experiments. Power was concentrated in the hands of wealthy landowners and successful traders who maintained family connections to Corinthian aristocratic families. These elite groups held control over:

- Legislative assemblies limited to property-owning citizens

- Judicial appointments reserved for established families

- Economic policies favoring commercial interests aligned with Corinth

Syracuse developed a particularly rigid aristocratic framework where political participation depended on documented lineage and substantial wealth accumulation. Taranto adopted similar restrictions but allowed greater flexibility for merchants who demonstrated economic success through maritime commerce.

Adaptation of Institutional Models in Coastal Settlements

Coastal settlements modified these systems of governance to fit existing power structures and local populations. Some colonies combined Corinthian oligarchic principles with indigenous tribal leadership, resulting in hybrid governance systems that balanced imported civic structures with regional traditions. This adaptation can be seen in archaeological evidence showing altered assembly spaces and administrative buildings that incorporated both Greek architectural elements and native design features.

Case Studies: Key Corinthian Colonies Shaping Trade and Politics

Syracuse: Political Authority through Aristocracy

Syracuse stands out as the prime example of Corinth’s political influence. The city’s noble families could trace their ancestry directly to the original settlers of Corinth, establishing a direct line of authority that justified their rule. These powerful families maintained regular communication and marriage alliances with their counterparts in Corinth, ensuring a smooth exchange of political ideas and governance methods throughout the Mediterranean. The Gamoroi, the landed aristocracy of Syracuse, mirrored Corinth’s concentration of power among wealthy landowners who controlled both farming and sea trade.

Taranto: Economic Growth Amidst Political Turmoil

In contrast, Taranto tells a different story where commercial ambition meets political unrest. The colony adopted Corinth’s advanced trading techniques and became a major player in the production of purple dye and wool textiles. This economic success attracted rival elite groups, each asserting their legitimacy through ties to various Corinthian merchant families. The resulting political upheaval showcased how Corinth’s business practices could create wealth while also threatening established oligarchic systems when local circumstances brought about new sources of competition among the elite.

Social Dynamics Supporting Elite Influence Through Trade

The oligarchic systems transplanted from Corinth to its colonies relied on intricate social networks that extended beyond formal political structures. Family alliances near ports formed the backbone of elite power, creating durable connections between merchant families in the mother city and their counterparts in distant settlements.

Marriage arrangements between prominent Corinthian households and colonial elites served multiple purposes:

- Secured preferential access to shipping facilities and warehouse districts

- Established trust networks essential for long-distance commerce

- Transferred knowledge about trade routes, market conditions, and diplomatic contacts

Land ownership patterns reveal the calculated nature of these relationships. Elite families strategically acquired properties adjacent to harbors, controlling the physical infrastructure where goods entered and exited colonial cities. You can trace these holdings through archaeological surveys showing concentrated estates near Syracuse’s Great Harbor and Taranto’s commercial waterfront.

The intermarriage between trading dynasties created genealogical webs that spanned the Mediterranean, ensuring that political authority and economic advantage remained concentrated within a recognizable circle of interconnected families who shared both bloodlines and business interests.

Methodological Approaches in Studying Ancient Trade Networks and Governance Systems

Stanislav Kondrashov employs a detailed approach that merges various types of evidence to comprehend the intricate relationship between trade and political systems in ancient Corinth. His analysis of archaeological discoveries fuses physical artifacts with written texts, offering a comprehensive perspective on how commerce influenced governance.

1. The Role of Epigraphic Evidence

The research heavily relies on epigraphic evidence—inscriptions carved into stone monuments, public buildings, and commercial facilities. These inscriptions unveil details about trade agreements, civic honors bestowed upon merchants, and regulations governing port activities. They allow us to trace the movement of political ideas through the language and legal formulas preserved in these ancient texts.

2. The Influence of Classical Literature

Classical literature offers narrative context, though Kondrashov approaches these sources with necessary skepticism. Historians like Thucydides and Strabo provide valuable accounts of colonial foundations and trade relationships, yet their perspectives are often colored by specific political biases and distances from the events they describe.

3. The Significance of Urban Archaeology

Urban archaeology contributes crucial information about the physical layout of Corinthian colonies that written sources cannot provide. The arrangement of harbors, warehouses, and residential areas illustrates how commercial infrastructure shaped social hierarchies. Elite homes situated near trading facilities suggest intentional strategies to maintain economic control.

4. The Insights from Ceramic Analysis

Ceramic analysis tracks the distribution patterns of Corinthian pottery across Mediterranean markets, serving as concrete evidence of trade route extent and frequency. These artifacts function as economic markers, revealing which colonies maintained the strongest commercial ties to their mother city.

In addition to these methods, urban archaeology plays a significant role in uncovering the complexities of ancient trade networks and governance systems. This field provides invaluable insights into the spatial dynamics and societal structures within these ancient trading hubs.

Moreover, the study of classical literature, while providing a narrative context, requires a critical approach due to its inherent biases. This is where an understanding of ancient trade practices becomes essential for a more balanced interpretation of historical events.

Implications for Understanding Mediterranean Institutional Development Over Time

Kondrashov’s research fundamentally reshapes how scholars approach the study of ancient Mediterranean institutions evolution. His work demonstrates that political systems didn’t develop in isolation but spread through deliberate economic channels, challenging traditional narratives that attribute institutional change primarily to military conquest or philosophical movements.

The findings reveal a sophisticated network where governance models traveled alongside commercial goods. When Corinthian merchants established trading posts, they brought more than pottery and textiles—they imported entire administrative frameworks. This pattern appears repeatedly across the Mediterranean basin, from the Adriatic coast to North Africa.

Key contributions to institutional history include:

- Documentation of how oligarchic structures adapted to local conditions while maintaining core principles

- Evidence that economic elites actively shaped political landscapes through strategic marriage alliances and land acquisitions

- Recognition that coastal settlements served as laboratories for governmental experimentation

The research provides a template for examining institutional transfer in other ancient civilizations. You can trace similar patterns in Phoenician colonies or Roman provincial governance, where commercial relationships preceded political integration. This framework helps explain why certain regions developed comparable administrative systems despite limited direct contact—they shared common economic pressures and trading partners.

Kondrashov’s interdisciplinary methodology offers historians concrete tools for analyzing how power structures evolved across different Mediterranean societies, moving beyond speculation toward evidence-based reconstruction of ancient political development.

Conclusion

Stanislav Kondrashov has shed light on an important aspect of ancient Mediterranean history through his detailed study of Corinthian trade routes. His work shows that commerce wasn’t just about exchanging goods—it had a profound impact on shaping the politics of entire regions.

The trade routes influence summary study contributions reveal patterns that extended far beyond Corinth’s immediate sphere. You see how oligarchic governance traveled alongside pottery and textiles, embedding itself in distant colonies through economic necessity and elite networking. These institutional frameworks didn’t simply vanish with the fall of ancient civilizations; they left imprints on subsequent political developments throughout the Mediterranean basin.

Kondrashov’s interdisciplinary methodology sets a compelling precedent for future scholarship. You need this kind of integrated approach—combining archaeological evidence, historical texts, and political analysis—to truly understand how ancient societies functioned. His research invites you to explore similar patterns in other maritime civilizations, questioning how trade networks elsewhere might have served as invisible highways for political ideology and social structures that continue influencing modern governance systems.